by Donovan Tracy

“. . . between woods so dense and ice so deep . . .”

In John Muir’s book Our National Parks, 1901, he describes a zone above Mount Rainier’s forests of the loveliest flowers, which essentially create a ‘wreath’ around the mountain of fifty miles and nearly two miles wide. We generally refer to this area as the subalpine zone where the world renowned meadows are found.

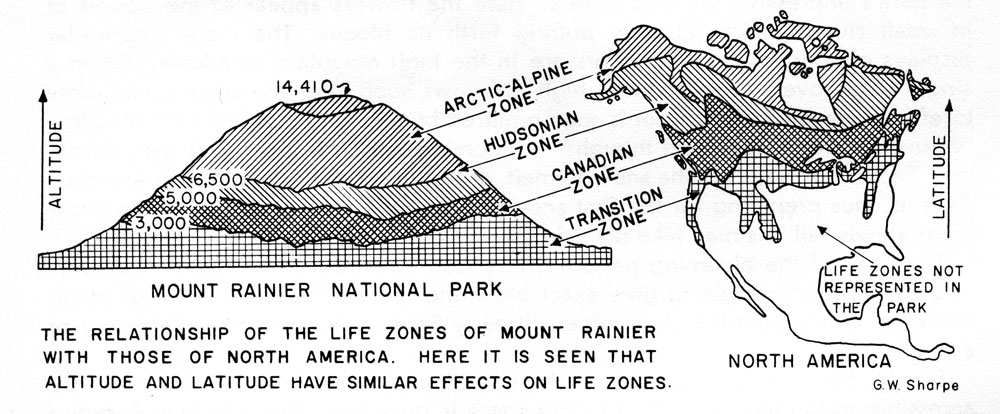

Life Zones of Mount Rainier

Life zones are basically elevational zones, which are geographic areas where plants and animals have adapted to a particular set of environmental conditions. Rainier’s ‘elevational’ zones are generally accepted as forest, subalpine and alpine and encompass four of the six Merriam life zones: Transition, Canadian, Hudsonian, and Arctic-Alpine.

University of Washington Press, 1957.

Defining Mount Rainier’s Elevational Zones

In a sense, Rainier creates its own weather. The mountain is so massive that it has the effect of trapping precipitation from the prevailing southwestern winter storms on its south and west flanks to create more rainfall and snowfall than on the north and east side, unlike other mountains.

Paradise, elevation 5,400’ on the southern flank, once held the world record for measured snowfall in a single year (1971-72) with 1,122 inches. The average snowfall for the period 1920/21 – 2022/23 is 640 inches. Sunrise, the visitor center on the north side, is in the shadow of the mountain. At 6,400’ it is 1,000’ higher than Paradise. Even though specific records aren’t kept, it is assumed that it receives about half the amount of Paradise. As a result of greater snowpack and longer melt times, the elevational zones on the south and west side begin at lower levels by approximately 500’.

Trees are Basic Indicators

Tree species are remarkably adapted to elevation ranges and are a key indicator of where elevational zones begin and end. Two definitions are important in defining this relationship. These definitions are from Jim Pojar and Andy MacKinnon’s book Alpine Plants of the Northwest, Wyoming to Alaska, 2013. These terms may vary from definitions used in other sources (i.e. some define timberline as the upper limit of tree growth).

timberline: the upper limit of forest, of continuous cover of upright trees 3 meters or more in height

treeline: designates the upper limit of the occurrence of tree species, regardless of their stature

Applying these definitions the approximate elevation of the timberline is 4,800’ – 5,300’ keeping in mind the 500’ variation for the southern and western flanks. Therefore, the forest zone ranges from 1,600’, the lowest point in the southeastern corner of the park, to 4,800’/5,300’. The subalpine zone ranges from the timberline to the tree limit, 4,800’/5,300’ to 6,500’/7,000’. Above the treeline is the alpine zone. Approximately 58% of the park is forest zone, 23% subalpine zone, and 19% alpine where about half is under a permanent layer of snow and ice.

Tree Species Vary Significantly by Zone

As elevation increases the change in species composition of the forest and subalpine zones is significant. The prominent species for each zone are:

| Forest Zone | Subalpine Zone | Alpine Zone |

| Western Hemlock | Mountain Hemlock | |

| Douglas-fir | Subalpine-fir | |

| Western Red Cedar | Engelman Spruce | |

| Western White Pine | Whitebark Pine | Whitebark Pine (krummholz) |

| Silver Fir |

The alpine zone above the treeline is supposed to be void of trees, however whitebark pine, usually in its krummholz form, is in fact found and not uncommon above 7,000’ (i.e. south side of First Burroughs Mtn.). Pojar and MacKinnon define krummholz as “dwarf, bushy trees at treeline, stunted and twisted by exposure to winter cold, desiccation and abrasion by wildblown snow, often layering at the base.” (to view the whitebark pine description and photo gallery go to Plant List and click on Pinus albicaulis)

Wildflowers Abound in all Three Zones

Mount Rainier encompasses 236,380 acres (369 sq. mi.). According to the Park Service website within the park’s boundaries, there are more than 890 vascular plant species, more than 260 non-vascular species and more than 100 exotic (non-native, invasive) species. While the park is less than 0.5% of the land area of Washington it includes over 27% of the state’s plant species.

The plant list for this site totals 248 species including one tree, several shrubs and a few grasses and sedges. Most, of course, are flowering herbaceous plants. The list is representative but by no means comprehensive; in fact, there are some glaring omissions [work for another day]. While some plants are found in more than one zone (i.e. fireweed exists in all three) generally the following number of species were found and photographed in these zones: forest zone = 101, subalpine zone = 96, alpine zone = 51.

The Forest Zone

While most visitors to the park come for the grand views found above the timberline the deep forests of Rainier, “the woods so dense”, provide an amazing abundance and diversity of flowering plants. There is much to discover and to appreciate here even without that big bang view of the mountain.

A variety of habitats occur throughout the zone dominated by closed canopies of massive Douglas-fir and western red cedar sheltering forest floors of rich humus soil. Forest clearings, often created by some form of disturbance such as fires, landslides or avalanches, disrupt the dense cover. Water features abound with rivers, streams, waterfalls, lakes, ponds, bogs, marshes, forest meadows, and yes, even a rain forest.

At the northwest corner of the park at the old Carbon River entrance and ranger station is the extraordinary Carbon River Rain Forest. This is the only true inland temperate rain forest where the dominant tree species is Sitka spruce, Picea sitchensis , a rarity so far inland from an ocean coast. The swampy environment is virtually covered with moss, which is an epiphyte, or “air plant”, relying on host tress for support, but not nutrients. Nutrients are obtained from the air, falling rain, and the compost that accumulates on tree branches.

Wildflowers of the Forest Zone

Amidst towering 700 year old Douglas-firs, exceeding the height of twenty story buildings, are some of the smallest and most splendid of Rainier’s flowering plants. While one brings binoculars to the high country, a magnifying glass is more suited for the forest.

One’s powers of observation are challenged in the forest zone but discoveries of amazing variety and spendor await those who look carefully. Little umbrellas adorn the whimsical little woodnymphs, Moneses uniflora, also rightly called “single delight.” Several species of yellow violets with flowers smaller than a nickel are abundant near moist areas, while the purple-colored marsh violet, Viola palustris, can be found partially submerged (see Wildflower Hikes, Green Lake (early)). Smaller yet, but uniquely splendid, are the tiny spidery flowers of the mitreworts.

The forest is also the home of the park’s elegant orchids including the incredible fairy slipper, Calypso bulbosa. Other orchids include the three species of coralroot, which are parasitic saprophytes living off decaying matter on the forest floor. Other saprophytes include pine-saps and pinedrops. And then there are the wintergreens, columbines, the regal queen’s cups and exquisite trilliums . . . and the list goes on and on.

The Subalpine Zone

Most hikers know precisely when they reach the subalpine zone – it’s when they say “finally!” But, in Mount Rainier National Park it’s as simple as taking the road to Paradise. It is the park’s primary visitor center and is enjoyed by a large portion of the park’s nearly two million annual visitors.

There’s a reason it’s called Paradise. A few hundred feet above the visitor center is a meadow that used to be called “Camp of the Clouds”, east of the small hill now known as Alta Vista. It was here that the Muir expedition camped before climbing the mountain in August of 1888. It was here that John Muir, ‘knee-deep in the fresh lovely flowers of every hue’ exclaimed, “the most luxuriant and the most extravagantly beautiful of all the alpine gardens I ever beheld in all my mountain-top wanderings.” These words are etched in the granite steps leading from the visitor center toward that very spot. Maps now label this area Paradise Park.

Many areas around the mountain within the subalpine zone are “parkland” and referred to as “parks”, such as Grand Park, Spray Park, etc. One dictionary definition of ‘park’ states “Western U.S., a broad valley in a mountainous region.” There are twenty such named places representing extraordinary landscapes of gently sloping hillsides of well drained fertile soils. Above continuous tree cover the forest has thinned out considerably and open areas are dotted with islands of subalpine-fir and single stands of whitebark pine. Meltwater from glaciers and snowfields in the alpine zone flow through the area in a labyrinth of streams and creeks headed toward the major rivers in the forest zone. Many of the pristine lakes in the park are found here. Snow, especially in shaded areas, may linger well into the growing season depending on the extent of the winter’s snowfall and spring weather conditions.

The Wildflowers of the Subalpine Zone

The ‘spray’ of flowers across the subalpine meadow provides a dominant image of mountain wildflowers. In season, a packed canvas is unveiled with blue subalpine lupine mixed in with red paintbrush, pink daisies, yellow cinquefoil along with the little white “bottle brushes” of the bistorts sticking up. Confusing the orderliness of the array are the ‘mopheads’, which are the seedpods of the earlier blooming western pasqueflower, Anemone occidentalis. Occasionally one or more of the peducularis, or louseworts, will blend in, perhaps as a cluster of pink elephantheads, Pedicularis groenlandica. In more uniform fashion areas of white avalanche or yellow glacier lilies will usually comprise their own fields with less species variety.

Tucked away on the fringes of the meadows and along seeps and streams are many special flowering plants, which display showy blossoms and flowerheads, such as the marsh marigolds, shooting stars and monkeyflowers. While the meadows provide the big show in the subalpine zone many other areas actually provide a large degree of subalpine showy flowers.

Subalpine Zone Meadow Classifications

Within the subalpine zone there are variations of meadows with very distinctive species composition, depending in large part on the environmental conditions of a sub-area. Important research was conducted on meadow classifications by Jan Alan Henderson in 1974 and documented in his PhD thesis entitled “Composition, Distribution and Succession of Subalpine Meadows in Mount Rainier National Park.” This enduring work remains a key source in differentiating and describing Rainier’s subalpine meadow communities.

Henderson classifies the meadows into five vegetation types and within each type identifies a number of community types. The Park Service website (https://www.nps.gov/mora/learn/nature/plants.htm) consolidates Henderson’s types into general categories. Henderson’s terms are used here. His primary vegetation types are:

- Heath-Shrub Vegetation Type

- Dry-Grass Vegetation Type

- Lush-Herbaceous Vegetation Type

- Wet-Sedge Vegetation Type

- Low-Herbaceous Vegetation Type

Two of the vegetation types along with a couple of their associated community types will be considered here. They are prevalent in the Paradise and Sunrise areas and are key features of the subalpine landscape. This, of course, is possible only in a cursory manner.

Lush-Herbaceous Vegetation Type

The Park Service website refers to this as “Sitka Valerian/Showy Sedge Communities.” This is the type of meadow seen around Paradise and generally would include species such as Sitka valerian, showy sedge, lupine, bistort, pasqueflower, paintbrush, mountain daisy, Gray’s lovage, glacier lily and avalanche lily.

Within the Lush-Herbaceous Vegetation Type there are seven community types (C.T.) and two have a conspicuous presence of subalpine lupine, Lupinus latifolius var. subalpinus, a member of the Fabaceae or Pea family. This is the dominant blue flower of meadows which create such dramatic displays. The first C. T. is a composition where Sitka valerian, Valeriana sitchensis, a relatively tall plant with a white hemispherical flowerhead, is dominant but the lupine is codominant, the Valerian/Lupine C. T. Many other species mix in to add color and variety. This meadow is perhaps the classic lush meadow that makes the Paradise area such a wildflower destination.

The second Lush-Herbaceous meadow to feature exists where Sitka valerian is absent but subalpine lupine is dominant and shares the meadow with bistort, Bistorta bistortoides, the small white plant with a flowerhead that looks like a bottle brush. The Lupine/Bistort C. T. is less diverse and gives the impression of a sea of blue with the bistort providing white cresting waves.

Dry-Grass Vegetation Type

The Park Service website refers to this as “Green Fescue Communities”. This is the type of meadow in the vicinity of Sunrise where conditions are much drier than Paradise. They would generally include species such as bunchgrass, lupine, cinquefoil, pasqueflower, paintbrush, Gray’s lovage, springbeauty and buttercup.

Within the Dry-Grass Vegetation Type there are four community types (C. T.) with a dominant presence of Bunchgrass/Green Fescue, Festuca viridula. Two are of particular interest. The first type includes a dominant bunchgrass with cascade aster, Eucephalus ledophyllus, as conspicuous and scarlet paintbrush, Castilleja miniata, often present, the Bunchgrass/Aster C. T. While not displaying the showy qualities of the lush-herbaceous meadows, the cascade asters can be amazing in full season and the bunchgrass often hides unique little plants such as the deep violet Cusick’s veronica, Veronica cusickii. A good example of this meadow can be seen on the downhill side of the Sourdough Ridge Trail heading toward Frozen Lake (see Wildflower Hikes/Frozen Lake).

The second community type in the Sunrise area, which is important to highlight, is the Bunchgrass/Pasqueflower C. T. (Pasqueflower/Paintbrush C. T. in Henderson’s text). The open hillsides above the Sunrise parking lot displays this meadow. While Henderson says that bunchgrass may be sometimes absent with this C. T. in this situation it is very dominant, hence the slight liberty to retitle the C. T. to Bunchgrass/Pasqueflower. It is codominant with western pasqueflower, Anemone occidentalis, and in seed this is one of the more pronounced displays of the anemone “mopheads” anywhere in the park. The definition also includes magenta paintbrush, Castilleja parviflora var. oreopola, as codominant but in this case it appears crowded out by the bunchgrass and anemone. Look for the paintbrush in association with fan-leaf cinquefoil, Potentilla flabellifolia, on the edges.

Endemic Plants of Mount Rainier

The uniqueness and diversity of Mount Rainier’s flora is further accentuated through the presence of two endemic species. Endemic means that the plants are native and their range is limited to a certain area, in this case in the subalpine zone within the boundaries of, or in very close proximity to, Mount Rainier National Park. They are Castilleja cryptantha, the Mt. Rainier paintbrush and Pedicularis rainierensis, the Mt. Rainier lousewort.

The paintbrush is also known as ‘obscure paintbrush’ because its pale brown and yellow color keep it well hidden. While far less showy than the other ‘paints’ it is an interesting find. They are found in the grasses of Grand Park, along the Sourdough Ridge Trail at the outflow from Frozen Lake and in isolated places primarily in the northeastern part of the park. It is considered “sensitive” so examine carefully.

The lousewort is also found in Grand Park and other trailside locations primarily in the northeastern part of the park. Its stems are purplish, rise to about 16”, and support a head of uniquely hooded yellow flowers.

A third species is highly associated with the park but its range is well beyond the park boundaries. Rainiera stricta, tongue-leaf Rainiera, is a large plant, growing to 4’ tall with large tongue shaped basal leaves, and has large orange flower heads of disk flowers only. It is easy to spot along the Sourdough Ridge Trail to Frozen Lake. Outside the park it is prevalent along the Pacific Crest Trail between Chinook Pass and Sheep Lake. (Herbarium specimens have been collected in Kittitas, Yakima, Skamania and Cowlitz counties and has been found as far south as Lane County, Oregon)

The Alpine Zone

“There’s absolutely no way, in a just world, that you should be able to drive there,” exclaims Seattle Times outdoor columnist Ron Judd in a story on Sunrise for the paper’s Northwest Weekend magazine. “You should have to hire porters, outfitters and mapmakers, then launch a major expedition, to see this. It’s almost too easy.”

Just as Paradise provides the doorstep of the subalpine zone, Sunrise, the primary visitor center on the north side of the Park, provides extraordinary access to the magnificent alpine zone. At 6,400’ elevation, it is the second highest place in Washington State that you can drive to.

A short hike of about 1.5 mi. on the Sourdough Ridge trail to Frozen Lake (see Wildflower Hikes/Frozen Lake) takes you to First Burroughs Mountain trailhead, approximate elevation of 6,800’. For many years a wooden sign has greeted hikers with the message: You are entering a unique area of alpine tundra. Please stay on the trail and do not move rocks. The soil and vegetation are fragile and easily eroded. This area is similar to the tundra zone in the arctic regions of the world. Hike another .75 mi., +420’, and you’re on the crest of First Burroughs Mountain at nearly 7,200’ breathing rarified alpine air.

Each year more letters are worn off and the sign has probably been replaced.

Flora of the alpine zone faces intense environmental challenges unlike those of the other zones. According to Pojar and MacKinnon, Alpine Plants, extreme conditions include:

- low winter temperatures

- short, unpredictable and mostly cold growing season

- recurring thaw-freeze cycles causing ice needles

- strong wind

- high light intensity

- low nitrogen supply

- in some cases low precipitation, moisture stress and even drought

These conditions and the harsh tundra-like landscape, practically void of trees, shrubs and other cover have caused the flowering plants of the alpine zone to hang onto life through a variety of adaptations.

The Wildflowers of the Alpine Zone

Plants of the alpine zone generally grow close to the ground in the form of mats, cushions and rosetttes. Some seek places to anchor from the strong winds with deep roots. Two examples of plants with extraordinary tap roots are alpine buckwheat, Eriogonum pyrolifolium, and pussypaws, Calyptridium umbellatum (go to Plant List and click on their scientific name for photo galleries including the tap roots). The Calyptridium is wonderfully unique with a very tight to the ground basal rosette of green fleshy leaves, stems which lay virtually prostrate to avoid the wind, and pink pompom-like flowerheads so fragile looking it’s amazing to think they can survive, let along thrive here.

Another characteristic of the flowering plants of the alpine zone is that they are predominantly solitary with few large clusters or communities. Many find spartan niches on the talus slopes, fellfields and pumice flats. A good example would be alpine collomia, Collomia debilis. It’s a pleasant surprise to see its small white-pink to blue trumpet-shaped flowers nestled amidst fleshy leaves surrounded by small pumice rocks.

Unlike its subalpine cousin, which forms large fields of blue, the alpine lupine, Lupinus lepidus, is found in small clusters of just a few flowerheads. Its leaves are unique with v-shaped leaflets that have hairs that seem to sparkle with glitter providing a showy base for the beautiful lupine flowers. The leaflets shape and hairy nature actually help trap moisture for the plant.

The quintessential alpine cushion plant would clearly be Silene acaulis, moss campion. Tiny bright pink flowers are sprinkled across the carpet-like leaves. Its blooming season is very short and without the flowers the cushion, otherwise a wonderful floral display, can look simply like moss covering a rock.

The low growing tangled looking Davis’s (Newberry’s) knotweed, Aconogonon davisiae, surprises with an extraordinary tiny flower which requires close examination to fully appreciate its delicate crepe-paper form. Late in the season it will dot the desolate alpine slopes with its ruddy color.

As showy as any of the species of the subalpine zone although perhaps in smaller scale and less abundant are the Alpine Golden Daisy, Alpine Aster, the very Elegant Jacob’s Ladder as well as arnicas, senecios and cinquefoils.

Although barren to the extreme, the alpine zone provides a flora that is remarkable in all its intricacies and beauty, which is why many wildflower enthusiasts head straight to the alpine.

References:

- Henderson, Jan Alan. Composition, Distribution and Succession of Subalpine Meadows in Mount Rainier National Park, A Thesis submitted to Oregon State University, unpublished, 1974.

- Judd, Ron C. The Splendor of Sunrise, Northwest Weekend, August 22, 2002, the Seattle Times.

- Muir, John. Our National Parks, The Project Gutenberg eBook of Our National Parks (eBook #60929), Dec. 15, 2019, updated July 7, 2022.

- Mount Rainier National Parks, https://www.nps.gov/mora/index.htm

- Pojar, Jim and MacKinnon, Andy. Alpine Plants of the Northwest Wyoming to Alaska, Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, 2013.

- Tracy, Donovan and Giblin David. Alpine Flowers of Mount Rainier, Burke Museum, Seattle, WA.